Summary:

The Sony PlayStation 1 videogame system upended Nintendo’s decade-long reign as the industry leader in videogames by outselling the Nintendo 64 three to one.

This happened because Sony embraced new technology, empowered their partners, and marketed to a different audience.

Prologue: U Can’t Touch This

June 1991. Sony is all smiles.

Every year, the major & would-be players in consumer electronics swagger into Summer CES.

It’s a tradeshow for technophiles to enlighten the masses with their latest & greatest. And Sony’s been doing all right for itself.

Around ten years earlier, Sony introduced something called a CD that kinda disrupted the entire music industry and dethroned vinyl records, the decades-old incumbent.

Along with the Walkman cassette music player, Trinitron TV, and other electronic epiphanies, Sony knows they’re upper crust.

When Sony casually announces a partnership with videogame tycoon Nintendo to produce a CD-based gaming system, it’s supposed to be a nonchalant humblebrag namedrop.

“Oh, you know, just getting into another multi-billion dollar industry. But who counts after video, audio, TV, music, film, and semiconductors, amirite?”

The next day at Nintendo’s press conference, it’s Nintendo’s turn to officially confirm the relationship from ‘Single’ to ‘In a relationship.’

In front of the national press and prominent peers, Nintendo announces they’re releasing the SNES (Super Nintendo Entertainment System), the follow-up to the ever-popular NES.

This is a big deal.

After videogames were labeled as a fading fad in the early 1980s, Nintendo single-handedly saved the industry with the NES released in 1985.

In less than seven years, it’s transformed Nintendo from a quaint Japanese toy company to a global entertainment phenomenon with $4 billion in yearly sales and 86% control of the videogame market.

There are nearly 30 million NES systems in living rooms and bedrooms and over 160 million games worshipped by children, their brothers & sisters, and their friends. Now it’s getting a sequel.

Sony gets to transform gaming with CDs, similar to what it’s done to music.

During the press conference, Nintendo paints the SNES in full glory: it’s a 16-bit system compared to the NES’s 8 bits— capable of superior graphics, cleaner sound, and deeper gameplay. For example, the NES can only showcase 25 colors onscreen colors. The SNES can do 10x that amount.

(Sony imagines the dream home they will build together.)

It will be released with a new Super Mario game whose cherubic mascot is already polling ahead of Mickey Mouse in popularity with American kids.

(Sony imagines the dream vacations.)

The SNES is the future of videogames, and the best way to future-proof it deep into the 1990s is to incorporate CD-ROM technology.

(Sony imagines the dream babies.)

And no other partner is more suited to be the other half of Nintendo’s CD heart than the co-creator of the CD, Philips.

Sony imagines the dream—wait, what the f—fantastic opportunities the SNES will provide as Nintendo continues to rave.

All eyes in the room go sideways on Sony. Calm down, Sony. Calm down. Maybe Nintendo was referring to Wilson Phillips.

“Blah blah… CD partnership with Philips…blah blah.”

OMG. This is really happening. Everyone’s gawking. Everyone’s smirking. Where’s the bucket of blood?

Sony just got dumped.

Publically. Embarrassingly. Especially for two Japanese companies whose culture is all about extreme politeness and jingoism, this is beyond humiliation. It’s a hearty smack to the face for all to witness.

Jesus, what will Toyota or Nikkon say?

And wait, Sony is the hot one here. They’re the cover model in every magazine. They’re the biggest name in consumer electronics.

Who the Handycam does Nintendo think they are to do this so openly? Without explanation? Without begging? Not even a pathetic it’s-not-you-it’s-me routine?

Oh, hell no. This is unforgiven. This is war. “Hasta La vista, baby” because it is on like Donkey Kong.

The Battle: Independence Day

In 1994, Sony released the PlayStation (PS or PS1, retroactively) in Japan, followed by a launch in North America and Europe in 1995.

The PS was a 32-bit home videogame system born out of a failed cooperation with Nintendo, the leader in videogames, after Nintendo backed at the last minute due to licensing concerns and worked with competitor Philips instead.

Spurned by public backstabbing, Sony persisted with the nascent project despite internal resistance, a brief flirtation to align with Sega, Nintendo’s #1 challenger, and even reconciliation with Nintendo.

Instead, Sony decided to enter the video game industry alone.

Despite being a consumer electronics colossus, Sony was the underdog in this fight. Similar big-name competitors like Philips and Panasonic were floundering to get into the space. Industry leaders Nintendo and Sega had loyal & rabid fanbases.

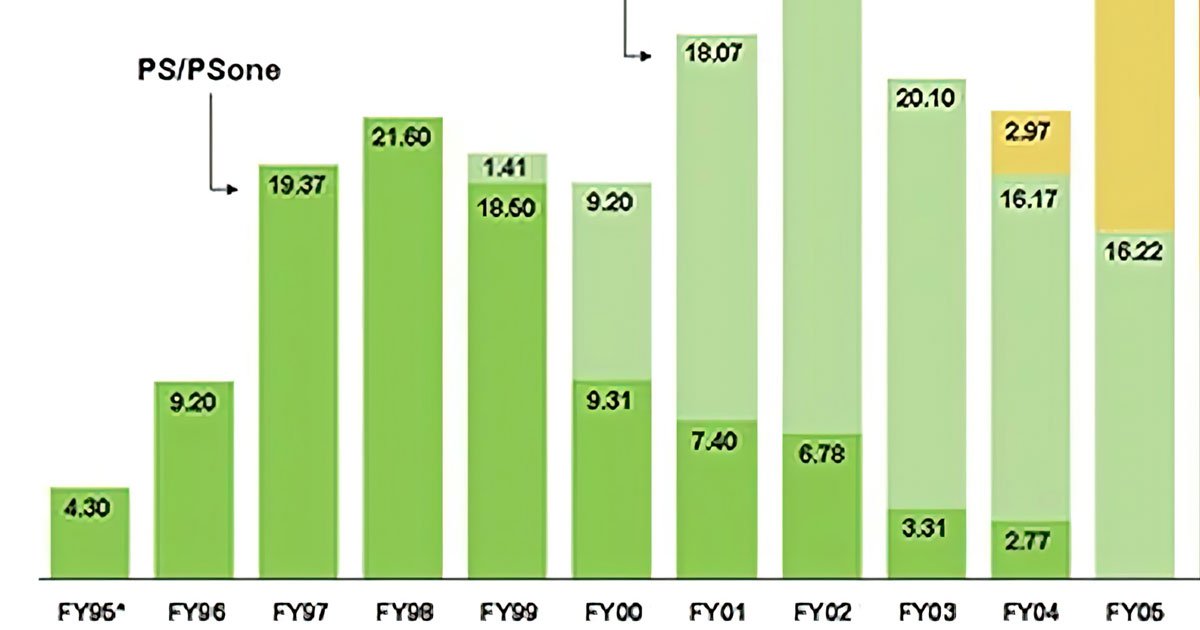

Yes, the PS had a two-year head start with over 5 million game systems worldwide heading into the summer of 1996. They even managed to stay competitive against Sega’s 32-bit system, the Sega Saturn. Yet Sony was bracing for the impact.

Everyone in the industry knew: It wasn’t a console war until Nintendo arrived at the party.

In late 1996 in America and early 1997 in Europe, Nintendo arrived fashionable late with the Nintendo 64 (N64), their next-generation 64-bit videogame console.

The N64 was the equivalent of a deity descending from the skies.

Silicon Graphics, a renowned high-end, high-performance 3D graphics workstation manufacturer, magically crammed its industrial brawns into a home machine for Nintendo. This was the same Silicon Graphics, whose technology helped create Toy Story, which launched the computer animation film industry.

The N64 had strong advantages over the PS: more bits (64 vs. 32), more RAM (4MB vs. 3MB), and more controller ports (4 vs. 2).

And it launched with its blockbuster title Super Mario 64, a game that introduced revolutionary 3D worlds and dumbfounded gamers.

Super Mario 64 was the Christmas hot item in 1996 America. It sold more than 2 million copies within three months.

Nintendo was confident history would repeat itself as it did with previous 16-bit console wars.

Upstarts like Sony or Sega would naively jump in and get the early buzz, early adopters, and a short-lived headstart. However, Nintendo would provide quality over quantity, and eventually, the masses would flock to Nintendo as they always did.

The king would keep his crown for another day, and all would be right in the kingdom of videogames.

Except by the end of 1997, it didn’t happen. And the same for 1998.

By 1999, it was apparent that Sony had dethroned Nintendo to become the new face of videogames.

The Winner: Sony PlayStation

By the end of 2000, the PlayStation sold over 80 million units worldwide. The Nintendo 64 sold under 30 million. When the 32/64-bit war ended, the PS not only outsold the N64 three to one but was the first video game system in history to sell over 100 million units.

How did Nintendo, the savior of the video game industry and industry bellwether for over a decade, lose to the newcomer Sony PlayStation?

The Reasons Why Sony Won

1. Better medium: CD vs. cartridge

The PlayStation used data CDs, while the Nintendo 64 used ROM cartridges. Nintendo’s omission of a CD disc drive is often considered one of the biggest reasons the PS topped the N64.

CDs had almost all the advantages over cartridges: cheaper to produce ($15 vs. $35, including licensing fees), faster to make (two weeks vs. three months), and held more memory (650 megabytes vs. 64 megabytes).

This translated to cheaper games on the PS, ranging from $50-60 USD, while N64 games went from $60-80 USD. For budget consumers, PS games would also get deeper discounts because the average cost to make a blank CD was $1.

For game developers, having 10x more storage capacity meant more assets. CDs held hours of video and audio content, making games more cinematic.

Before the era of CD-based gaming, most games were confined to pixelated graphics and the audio bleeps & bloops of 8-bit and 16-bit gaming. For the occasional game with vocals or lyrics, most were one-liners or, at its finest, “da bomb” theme songs.

The poster child for the CD vs. cartridge debate was Final Fantasy 7, a popular Japanese role-playing game (RPG).

Its predecessor, Final Fantasy 6, was a Nintendo exclusive that sold over 3 million copies on Nintendo’s previous console, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.

Naturally, its sequel, Final Fantasy 7, was assumed to appear on the N64.

However, Squaresoft, maker of the Final Fantasy series and other top-selling RPGs, had an ambitious new direction for the series as the generation shifted from 2D to 3D. It required much more memory than the N64 could provide.

Squaresoft chose to develop for the PlayStation, shocking the industry and establishing a path for once-loyal Nintendo third-party developers to jump ship.

Final Fantasy would sell nearly 10 million copies. The game spanned over three discs. One Final Fantasy 7 ad directly addressed the CD vs. cartridge debate by claiming the game would have cost $1,200 to run on a cartridge (over $2,200 in today’s money).

By the end of their lifecycle, over 4,000 games were produced for the PS. The N64 had slightly less than 400.

2. CGI revolution

As mentioned, PlayStation CDs held 10x more memory storage than the Nintendo 64 carts. Although graphics and gameplay were relatively comparable, the difference was the amount of pre-rendered CGI (computer-generated imagery) videos PlayStation games contained.

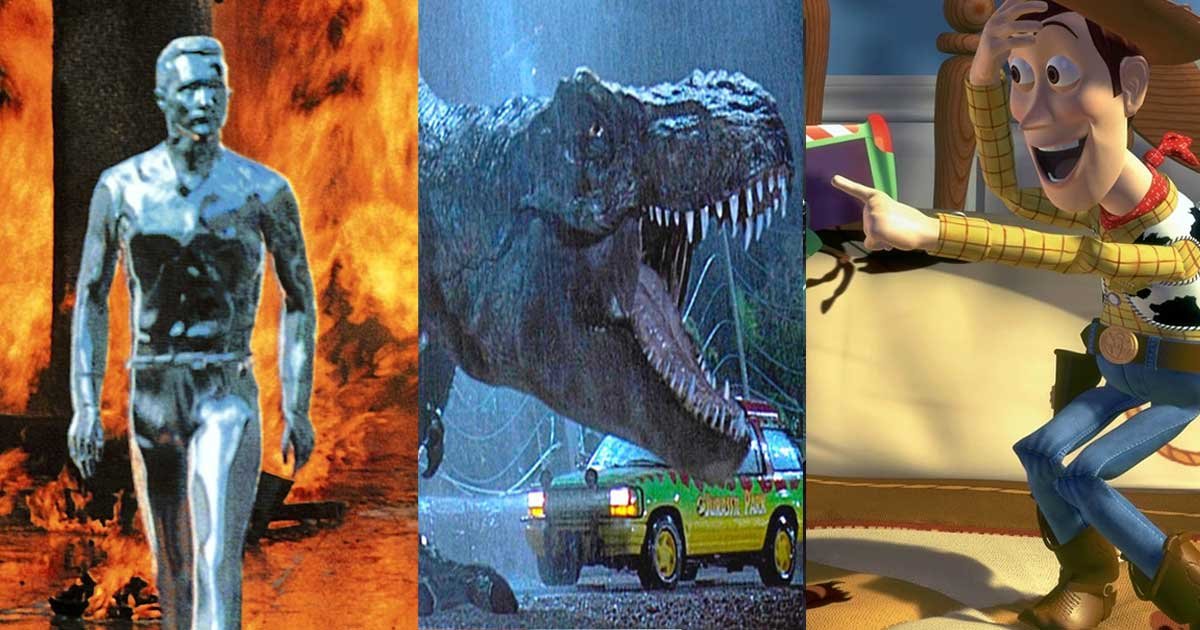

CGI in early to mid-1990s blockbuster films transformed Hollywood and influenced videogames.

Terminator 2 featured a liquid metal shape-shifting villain relentlessly chasing after John and Sarah Connor (top grossing movie in 1991). Dinosaurs roamed the earth again in Jurassic Park (top grossing film in 1993). Toy Story revealed the secret lives of childhood toys (the third highest-grossing movie in 1995).

The maturity of CGI & special effects with the advent of the CD allowed the 32/64 bit revolution to showcase—using the 1990s buzzwords—pre-rendered graphics, full motion video, real-time 3D, textured polygons, CD-quality sound, and cinematic gaming, to name a few.

Games could be like movies.

And for gamers graduating from the 8-bit and 16-bit era, it was a significant selling point, even if it was watching extended cutscenes and videos.

Though dated by today’s standards, it was eye candy for a generation raised on bleeps and bloops. Here are samples of PS cutscenes featuring games Tekken, Resident Evil, and Final Fantasy 8.

3. Better relationships: Developer love

With a near-monopoly of the videogame industry during the 8-bit and 16-bit generations, Nintendo enforced steadfast policies for their third-party developers.

For example, with the NES, only Nintendo had the authority to produce game cartridges. Nintendo required a minimum order of 10,000 cartridges with manufacturing costs up to $14 USD per cartridge and a 20% licensing fee—all paid in advance.

(A minimum order with Nintendo would cost a little over $300,000 USD in today’s money, excluding development, licensing fees, marketing, and other expenses.)

Even then, third-party companies had to submit their games to Nintendo for evaluation. After a review, Nintendo provided “suggestions” to improve the game and decided how many cartridges the third-party developer would actually receive. Cartridges were produced in Japan, so it was a minimum of 3 months before finally receiving them.

Other restrictions, like a two-year exclusivity clause and a limit of only five games published per year, felt more like policing than free trade.

Nintendo was also accused of creating artificial cartridge shortages to create greater demand for Nintendo games. This upset all developers.

Small developers felt Nintendo gave preference to bigger developers. Bigger developers were angry for not receiving the total amount of stock they requested, especially during the busy holiday season. And all developers had to compete against Nintendo’s own top-selling software.

Nintendo ultimately softened its licensing agreements when Sega became a real competitor, but even then, Sega was trying to be like Nintendo—another monopoly.

Sony took the road less traveled approach.

Sony understood hardware. Software wasn’t a forte.

Instead, Sony serenaded third-party developers by making a deal they couldn’t refuse: offer much lower manufacturing & licensing fees than Nintendo, provide better support, and let third-party developers make any games they wanted without a carrot-and-stick system like Nintendo’s.

Sony was about partnership. With the 3D revolution about to upset the old 2D guard of yesteryear, Sony was happy to handhold to the new generation.

By the time the PlayStation launched in America, they had signed 270 Japanese and 100 American developers.

4. Maturing audiences: Kids grow up

Nintendo dominated the videogame industry for two console generations from 1985 to 1996. Making family-friendly games helped the company gain favorable comparisons to Disney. All kids worshipped Mario.

But kids grow up.

The previous generation showdown between 16-bit Super Nintendo Entertainment System and the Sega Genesis highlighted the rising tide for titles that mom and dad wouldn’t approve of.

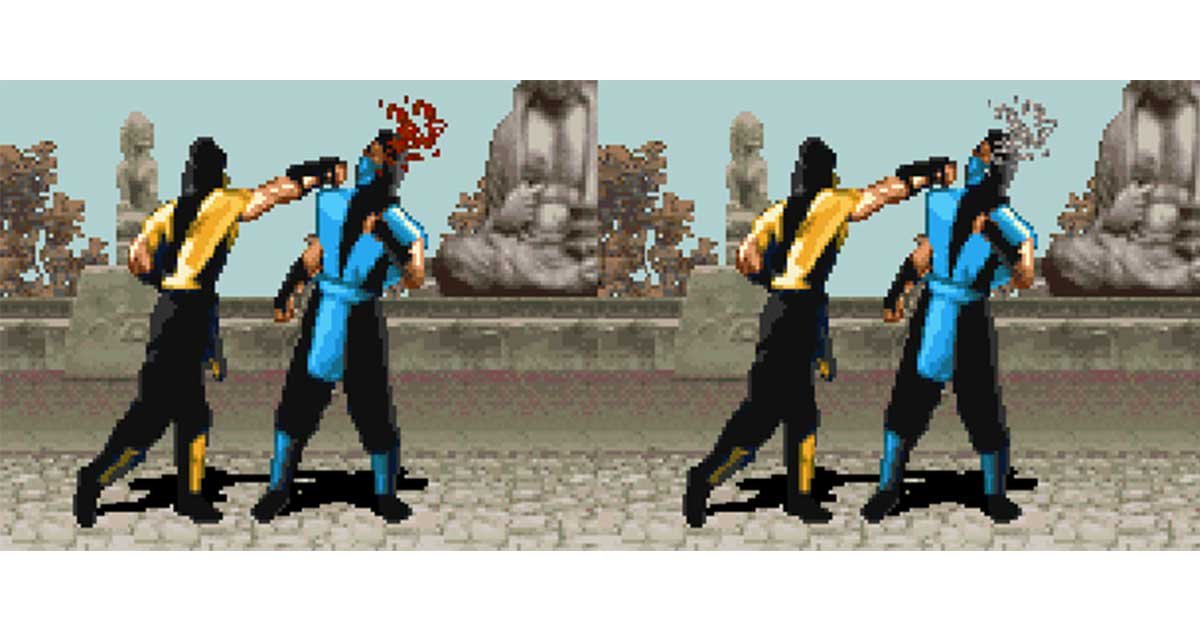

The tipping point was a game called Mortal Kombat, a fighting game where contestants fought each other to a bloody death.

Whereas previous games were often depicted as cartoon violence, Mortal Kombat featured digitized characters glorifying its violence with beheadings, electrocution, and tearing still-beating hearts from opponents’ chests.

When it launched on home systems, Nintendo heavily censored Mortal Kombat on the Super Nintendo. For example, it recolored all red blood to grey sweat and defanged the game’s brutality. This further enforced the image of Nintendo as a kid’s company but helped Sega’s edgy image.

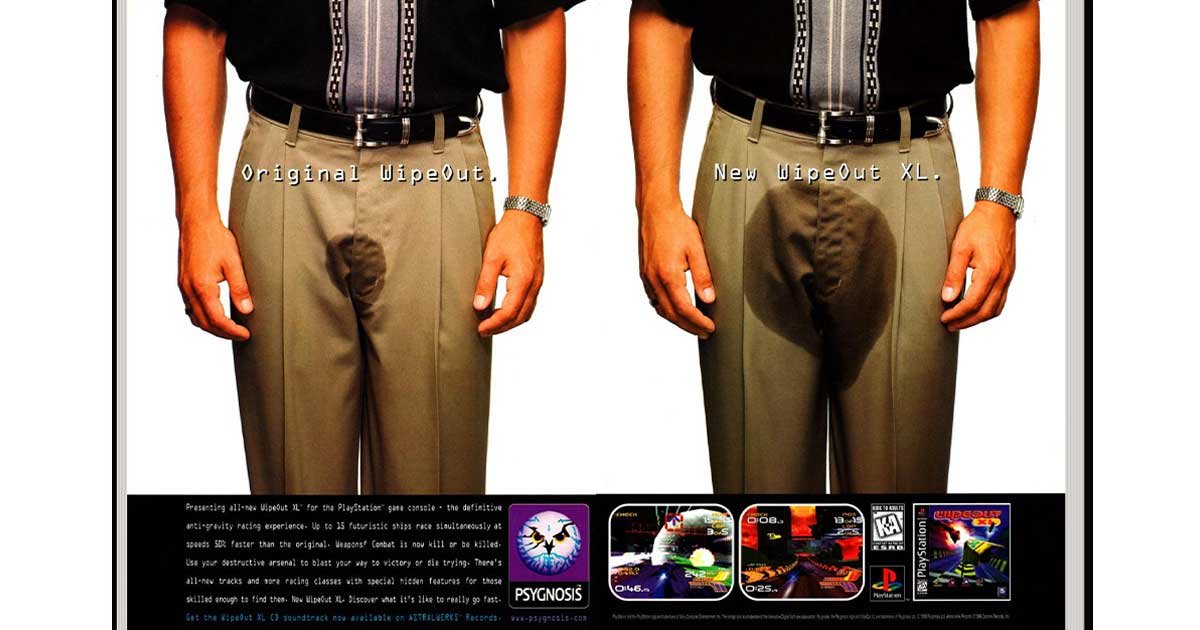

For the 32/64-bit war, Sony continued and expanded on Sega’s strategy of targeting older kids, teenagers, and young adults.

Characters and storylines grew beyond Nintendo’s save-the-princess trope.

Top-selling titles on the PlayStation, like Tomb Raider (objectified heroine), Metal Gear (warfare & political themes), and Resident Evil (flesh-eating zombies), proved the changing taste for more mature games.

Even family-friendly mascot characters like Crash Bandicoot had a rebellious streak.

Sony’s marketing was easy: Nintendo was for little kids. Sony was for gamers who wanted depth.

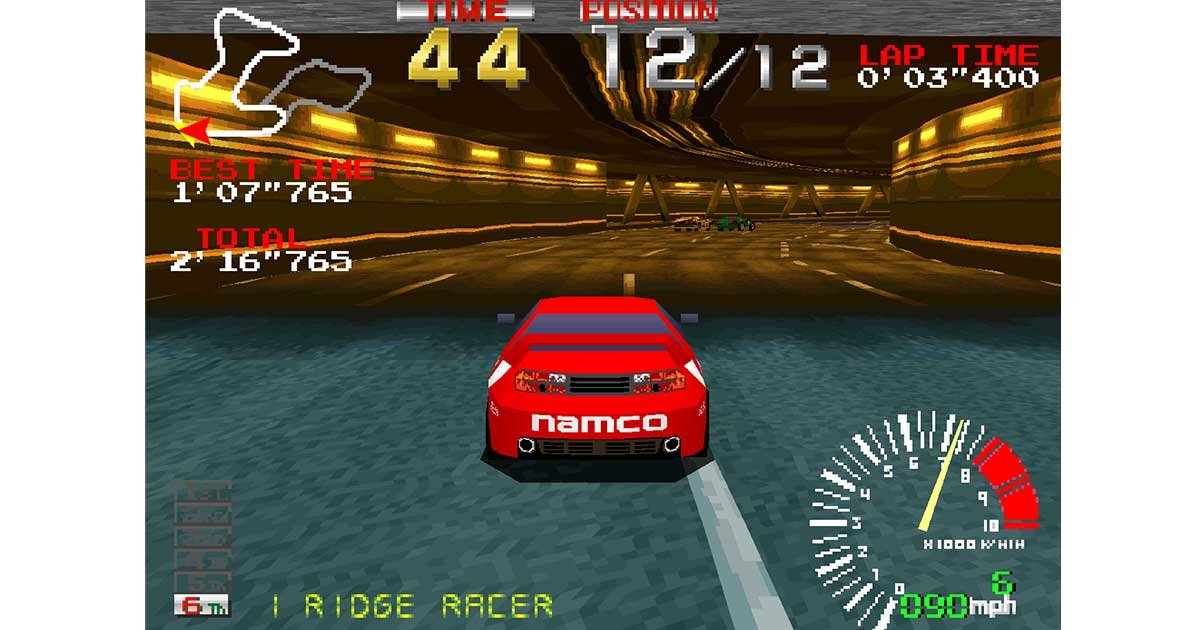

5. Steal like a thief: Rumble young man rumble

For every new console Nintendo launched, the company introduced innovations to its game controllers—many of which are standard across all gaming platforms today. The D-pad, shoulder buttons, and four-button layout were part of Nintendo’s evolution.

For the Nintendo 64, Nintendo introduced an analog stick to control characters in 3D spaces and an add-on device called the Rumble Pak, which would vibrate and give gamers another level of immersion.

The PlayStation had none of these features. The analog stick was a sore point for Sony, especially for a system that marketed itself as an advanced 3D gaming system.

3D games could be played without using an analog stick, but an analog stick made the experience much more intuitive. Nintendo had the advantage.

In response, Sony released the Dual Shock controller, which featured two analog controls and built-in rumble functions. This gave the PS parity and made the N64 controller look expensive since its Rumble Pak was an add-on accessory.

Besides controllers, Sony took what worked for the competition and added their spin.

For the launch of the PlayStation, Sony leaned on Ridge Racer, a 3D racing game, and Battle Arena Toshiden, a 3D fighting game, to combat Sega Saturn’s popular Daytona USA and Virtual Fighter— a 3D racing game and a 3D fighting game.

Crash Bandicoot was Sony’s mascot answer to Nintendo’s Super Mario and Sega’s Sonic the Hedgehog.

The Rebuttal

Sony was going to be a threat eventually.

Although Nintendo’s “betrayal” of Sony and their failed partnership is often cited as the starting point of Nintendo’s loss of dominance, it had already begun.

In America, the Sega Genesis proved there was enough room for two major players, battling the Super Nintendo Entertainment System to nearly 50% of the market.

Even if Nintendo had agreed to continue its partnership with Sony, it would have been Sony’s Trojan Horse into the industry because Sony intended to get into the hardware business eventually. This is similar to what Microsoft did with the Sega Dreamcast before launching its own console, the Xbox.

Sony’s goal was to become an entertainment powerhouse when it purchased Colombia Pictures (movies) and CBS Records (music) in the late 1980s.

The videogames industry was next.

Nintendo wasn’t worried about Sony because they had already beaten another Japanese electronics conglomerate.

NEC, the largest semiconductor manufacturer in the world and a top-five PC maker during the late 1980s, got into the videogame market with the TurboGrafx-16 (PC Engine in Japan).

NEC, like Sony, had deep pockets and expert hardware knowledge. However, the company lacked software knowledge— like Sony—and failed to disrupt Nintendo’s business.

Nintendo viewed Sony as another also-ran.

Cartridges live on.

Nintendo’s decision not to use CD is a significant reason why the Nintendo 64 lost the battle. But the company had its reasons: all previous attempts to use CD were unsuccessful. The Sega CD, TurboGrafx-CD, Panasonic 3DO, Atari Jaguar CD, and Philips CD-I failed with high hardware prices and poor software titles.

Nintendo’s investment in the cartridge faltered with the Nintendo 64 but proved to be right in its handheld systems from Gameboy to its current handheld/home system hybrid, the Nintendo Switch.

The Nintendo Switch has sold over 122 million systems and will most likely end up as one of the top 3 video game consoles of all time.

Although successful in disrupting Nintendo’s console hardware business, Sony’s strategy to use CDs in its handheld war vs. Nintendo resulted in defeat despite having superior hardware. [Author’s Note: Maybe a sequel article?]

Necessity is the mother of all invention.

After losing to Sony and then newcomer Microsoft’s Xbox in the early 2000s, Nintendo could no longer compete in the cutting-edge business. This helped the company refocus on fun and innovation rather than powerful hardware. The results were resounding comebacks with the Wii (motion controls), DS (dual screens), and Switch (handheld/home hybrid).

The Nintendo Wii outsold Sony’s PlayStation 3 and Microsoft’s Xbox 360 (7th generation). The Nintendo Switch has outsold Sony’s PlayStation 4 and Microsoft’s Xbox One (8th generation).

Kids grow up…. then have kids.

Nintendo’s family-friendly strategy help the company become a household name. It stalled growth during those “adolescent” and “young adult” years as gamers moved onto PlayStation and Xbox. However, once those kids became parents, a new audience emerged out of nostalgia and safe entertainment.

People, like videogame systems, have a next generation.

The Takeaways

1. Lean into the future, especially if it’s disruptive.

As the old saying goes, “What got you here won’t get you there.”

Business case studies are littered with once-dominant companies dismissing future threats & opportunities: Blockbuster Video and the internet, Kodak and the digital camera, Toys R Us and e-commerce, etc.

Success builds confidence but also a type of conclusiveness—thus, a limiting mindset correct about today’s realities but ignorant of tomorrow’s possibilities.

CDs had already transformed the music industry and were going mainstream with personal computers. It was “inevitable” it would do the same for gaming. Yet Nintendo dismissed it and gave Sony a considerable advantage to disrupt.

Industry leaders should focus on the present but also hedge bets on the future—even when it does affect short-term goals & profit. Disruption happens slowly but its effects are immediate when it happens.

2. Really, really understand your audience.

Many companies talk about valuing their customers but often don’t understand (really understand) the voice of their customers. Nintendo’s audience was growing older and there was a demand for more mature games.

Sony followed where the potential customers were, created messaging that resonated with them, and built a valuable brand name with the PlayStation.

Too many companies focus on products & services as branding, but the best branding is answering the customer’s WIIFM (what’s in it for me). That builds trust, which builds the brand’s name.

3. Learn how to win friends & influence people.

Nintendo’s top-down relationships with their third-party developers was acceptable when the company controlled a majority of the market.

Of the 127 games that sold a million copies or more across the NES and SNES, Nintendo was the publisher for 59 of those titles. The other 68 blockbuster games were from their partners. The same partners eventually flocked to Sony when given better conditions.

Remember that the “rising tide lifts all boats.”

Leveraging partner talents like Amazon’s Fulfilled by Amazon or Apple’s App Store helped both ecosystems grow and profited all parties involved.

Even when in the dominant position, create trust and build rapport with partners. The small things eventually add up.

Side Stories

What happened to the other competitors in the 32/64 bit war?

Sega reached its peak in the 16-bit war with Nintendo. After a lackluster 32-bit showing with the Sega Saturn and an underperforming successor in the Sega Dreamcast, Sega exited the hardware business and became a third-party software developer.

Philips’s partnership with Nintendo turned out to be short-lived. Their CD add-on to the Super Nintendo never was released, and their CD-I platform never took off.

The 3DO (championed by Panasonic), Atari Jaguar, and NEC TurboGrafx were commercial flops.

Who is Ken Kutaragi?

Ken Kutaragi is the father of the PlayStation. His uphill battle to get Sony into the videogame business and launch the PlayStation is worthy of a long case study.

How big is the videogame market today?

The videogame industry is worth over $200 billion worldwide. The smartphone and mobile games market is bigger than the home console and PC market combined.

Who are the other major hardware players in the videogame market?

Following Sony’s lead, Microsoft entered the videogame industry with the Xbox with four generations of systems. Google and Amazon released cloud-gaming with limited results.

What does the future of videogames look like?

Virtual reality, augmented reality, metaverse, NFTs, etc., are some buzzwords used to describe gaming in the next 10-20 years. With faster wireless speeds, streaming technology has the ability to transform gaming anytime, anywhere, potentially becoming platform-agnostic.

Leave a comment